- Home

- Аукционы открытые

-

Аукционы закрытые

- Coins & Medals

- Philately

- Antiquities

- Old Masters

- Jewellery, Silver, Watches

- Ancient and Modern Glyptic

- Ancient Porcelains and Ceramics

- Antiques

- Modern & Contemporary Art

- 20th Century Design and Decorative Arts

- Prints and Multiples

- Asian and Tribal Art

- Photography

- Medieval Art

- Ancient Frames

- Fashion, Textiles & Luxury

- Books, Autographs and Memorabilia

- Wines and spirits

- Oddities, Curiosities & Wonders

- Info

- Live Auction

- Home

- Auction 53

- 59 AN EXCEEDINGLY RARE AND EXTREMELY IMPORTANT CHINESE ...

Лот 59 - Auction 53

Описание

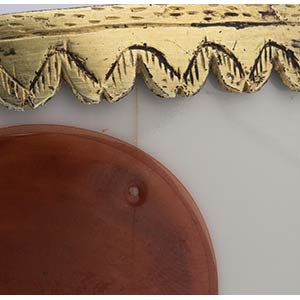

AN EXCEEDINGLY RARE AND EXTREMELY IMPORTANT CHINESE PORCELAIN CUP WITH A FINE GILT SILVER MOUNT

the cup Jiajing period (1522-1566), the unmarked mount probably English 1580-1585 circa

decorated to the exterior with four large red circular medallions on the white glazed body, the porcelain cup is supported by a slender stem rising from a circular domed foot and secured by four vertical pierced straps, the rim underlined by a scalloped edge, the whole mount enriched with finely engraved, casted and chased details, the foot with masks alternating to fruits, the mid section of the stem with three lion masks with movable rings in their mouths and three shells, the four vertical stripes on the upper section terminating with Bacchanal masks.

13,3 x 9,3 cm

Price on request

Provenance: Elisa Baciocchi (1777-1820), Granduchess of Tuscany and sister of Napoleon Bonaparte; acquired by Francesco Lugrammi, high official of the Kingdom of Italy, and thence to his son Giulio Lugrammi (1876-1958), General Commander of the Port of Marseilles and senator of the Kingdom of Italy who participated to the 1919 Peace Conference in Paris, thence to his son (1906-1991) and grandson.

This cup is a masterpiece, from many points of view.

Its main importance, however, is probably the story it tells. A very long story, lasting for more than four centuries. A story which involves high personages from at least two continents, Asia and Europe. From its first owner, possibly the Chinese Emperor Jiajing (reign 1522-1566) to probably Elizabeth Queen of England (1533-1588), from Elisa Baciocchi Granduchess of Tuscany and sister of Napoleon, to the Lugrammi family, which proudly owned this piece for two centuries.

Together with these very influential names in the world history, it tells us also about a crucial moment in the fascinating story of the encounter between two very distant cultures, China and Europe.

From the 14th century porcelain has surely been the most precious material which could arrive to Europe from China, this is widely known. From the epoch of Marco Polo onward, Chinese ware became the most desiderable good for all the European princes. Before the beginning of the direct trade between Asia and the Portoguese from the early 16th century, the number of Chinese porcelains which reached Europe was scarce. Even if they were not able to recognise the real composition of that material, the most influential members of the European élite perfectly understood the extraordinary qualities of Chinese porcelain, its thin and white body, its characteristics of being waterproof and the vividness of its enamelled or moulded decoration with motifs completely different from anything seen until then.

Chinese porcelain was simply precious, and it was then worthy enough to be enriched with metal mount, often realised by the best artists specialised in the working of metals. The rarity of Chinese porcelain and the preciousness of the metal mounts were qualities then combined to create extremely fine objects proudly exhibited in the most important Cabinets of Curiosities (Wunderkammern), those rooms where the European princes preserved their most valued treasures.

Great part of the still existing Chinese porcelains arrived in Europe in the 14th and 15th centuries presents in fact a metal mount, or was originally provided with such an embellishment, as for example the famous “Gaignières-Fonthill” bottle vase (Dublin, National Museum), given as a gift in 1381 by Louis I of Hungary to Charles III King of Naples (A. Lane, The Gaignières-Fonthill Vase. A Chinese Porcelain of about 1300, in “The Burlington Magazine”, CIII, 1961, 697, pp. 124,-132, pl. 2-11), or the céladon-glazed cup now in the Hessisches Landesmuseum in Kassel, acquired from Count Philipp von Katzenelnbogen around 1433-34 and certainly mounted before 1453 (Porzellan aus China und Japan. Die Porzellagalerie der Langgrafen von Hessen-Kassel, Kassel 1990, pp. 10-11, 216-218).

The use to enhance Chinese porcelain with metal mount continued also in the later centuries, even if the amount of imported porcelains from China dramatically grew with the advent of the various European East India Companies in the 16th and 17th centuries, reaching a peak in 18th century France. The style of these mounts obviously changed according to the development of the European taste.

The gilt silver mount which embellished the present cup shows stylistic features which immediately recall late Renaissance and Mannerist canons, for the presence of decorative motifs such as the typical grotesques interlaced with lion masks, escallops shells and Bacchanal masks.

A taste that can be related to the period of reign of Elizabeth, Queen of England and Ireland from 1558 to 1603. We know from documentary evidence that the Tudor Queen received as gifts in the 1580’s a number of mounted porcelains (A. Jefferies Collins, edited by, Jewels and Plate of Queen Elizabeth I, London 1955, p. 592, n. 1582), among them the Chinese bowl now in the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York (inv. n. 68.141.125a/b, Gift of Irwin Untermyer, 1968), whose mount is presumably the work of one of her favourite goldsmiths, Affabel Partridge. The mount of the cup in the Metropolitan Museum cannot be compared with the unmarked mount of the piece discussed here, this last one being more complex in its general conception and clearly richer in its decorative details. However, its stylistic features are those typical of the artists working in Europe at the end of the 16th century, also in England at the court of Queen Elizabeth, and there are some possibilities it could be also a work of the already cited Affabel Partridge.

The earliest known Chinese porcelain mounted in England is the “Lennard Cup”, so-called because it was owned by Samuel Lennard (1553-1618), lord of the manor at Wickham Court, West Wickham, Kent (British Museum, Percival David Collection: see S. Pierson, Percival David Foundation of Chinese Art. A Guide to the Collection, London 2003, p. 71, n. 58). The porcelain is Jiajing period, the beautiful mount has a London hallmark which allows to date it to 1560-70. From a stylistic point of view, despite many differences, it shares the same chronology with the cup here presented.

Yet regarding the mount, it seems useful to have a comparison also with the two so-called “Von Manderscheidt” cups, one sold in London by Sotheby’s (5 february 1970, lots 169, 170), the other one in the collections of the Victoria & Albert Museum (R. Kerr, Chinese Porcelain in Early European Collections, in Encounters. The Meeting of Asia and Europe 1500-1800, exhibition catalogue edited by A. Jackson and A. Jaffer, London 2004, pp. 44-51: p. 48, pl. 4.4). An inscription on one of the bowls records that the two pieces were mounted in 1583 in memory of Count Hermann von Manderscheidt for the will of his brother Count Eberhart who very probably acquired them a year before while travelling to Jerusalem, presumably in Turkey. Even if these two porcelain cups are from Jiajing period as the bowl here discussed, the style of their decoration is not comparable, while there are many affinities in the taste of the mount, decorated with groups of fruits and masks.

It is significant in the context we are discussing also the resurgence of diplomatic relationships between England and the Ottoman Empire during the reign of Queen Elisabeth. The two countries signed a treaty in 1580 with the aim to establish better commercial links, thanks to the activity of William Harborne (d. 1618) who was appointed ambassador in 1586. At that time the Turkish sultans have already amassed a great quantity of Chinese porcelains, the base of the fabulous collection now in the Topkapi Saray Museum in Istanbul. The presence of a bowl very similar to the one we are discussing here in that collection (R. Krahl, Chinese Ceramics in the Topkapi Saray Museum, 2 volls, London 1986: II, p. 824, n. 1658), could be a proof regarding the provenance of our unmounted Chinese cup from there, even if there is no documentary evidence for this hypothesis.

The Topkapi Saray Museum cup is dated to Jiajing period, even if it is unmarked. Its main decorative feature is the presence of the red round medallions to the exterior of the walls. This motif – which could also be associated to the sun, appearing as a decoration on garments directly referred to the Chinese emperor, the Son of Heaven (天子, tianzi) is typical of a group of bowls produced in Jingdezhen toward the mid 16th century, very much appraised also in Japan where the motif takes the name of akadama (literally “red dot pattern”). Sometimes the bowls of this type present a supplementary gilt decoration, and this is the reason because they are known with the Japanese definition of kinrande. Bowls with kinrande style decoration were also among the Jiajing period porcelains that reached Europe from the mid 16th century, as for example the two cups from the Castle of Ambras (W. Seipel, Exotica. Portugals Entdeckungen im Spiegel fürsstlicher Kunst- und Wunderkammern der Renaissance, exhibition catalogue, Wien 2000, n. 209).

Traces of an original gilt decoration could be seen also on the exterior of a large bowl (22 cm diam) now in Palazzo Pitti, Florence (F. Morena, Dalle Indie orientali alla corte di Toscana. Collezioni di arte cinese e giapponese a Palazzo Pitti, Florence 2005, n. 44, pl. XI). This bowl belonged with many probabilities to Ferdinando I de’ Medici (1549-1609), who amassed an important collection of Chinese porcelain already while he lived in Rome as a cardinal, before 1587 when he became Granduke of Tuscany: some pieces of his collection were sent as a gift to Christian of Saxony in 1590 and are now in the Porzellansammlung in Dresden (L. Reidemeister, Eine Schenkung chinesischer Porzellane aus dem Ende des 16. Jahrhundert, in “Ostasiatische Zetschrift”, 1933, pp. 12-16). This Florentine bowl shows a decoration of a large red round medallion to the centre of the interior and six other red dots to the exterior, just below a red stripe to the rim and a band of light green leaves toward the base. The bowl has a Jiajing six characters mark to the centre of the base.

Despite the differences in dimensions and in some details of the decoration, the Pitti Palace example and the bowl here presented certainly belonged to the same Chinese porcelain family. This comparison allows to take into consideration the hypothesis that also the smaller mounted cup could have a Jiajing mark, but this have to remain a mystery because of the difficulties to dismantle the piece.

In any case - the bowl mark or unmarked, the mount with a name or unnamed - what is certain is the terrific historical and artistic importance of this piece. To understand, it could be enough to think just for a moment to the personages who handled it: emperors, queens, duchesses, high dignitaries and all those other persons who surely had in their hands and that we still didn’t know.

PRICE ON REQUEST

Используйте форму для регистрации или введите логин в правой части формы.

За дополнительной информацией обращайтесь info@bertolamifineart.com

Политика использования файлов cookie

Политика использования файлов cookie

Этот сайт использует файлы cookie для улучшения взаимодействия с пользователем и сбора информации об использовании сайта. Существуют также файлы cookie, которые можно использовать для выбора персонализированной рекламы и рекламного контента. Вы можете ознакомиться с нашей политикой использования файлов cookie, принять все файлы cookie и продолжить просмотра, нажав "Принять" или измените свой выбор, нажав "Настроить".

Политика использования файлов cookie

Файлы cookie

Чтобы этот сайт работал должным образом, мы иногда устанавливаем на ваше устройство небольшие файлы данных, называемые " cookie ". Большинство крупных сайтов делают то же самое.

Что такое файлы cookie?

Файл cookie - это небольшой текстовый файл, который веб-сайты сохраняют на вашем компьютере или мобильном устройстве во время их посещения. Благодаря файлам cookie сайт запоминает ваши действия и предпочтения (например, логин, язык, размер шрифта и другие параметры отображения), чтобы вам не приходилось повторно вводить их, когда вы возвращаетесь на сайт или переходите с одной страницы на другую.

Как мы используем файлы cookie?

Сторонние файлы cookie

Google Analytics

Этот сайт использует Google Analytics для сбора информации об использовании пользователями его веб-сайта. Google Analytics генерирует статистическую и другую информацию с помощью файлов cookie, хранящихся на компьютерах пользователей. Информация, полученная в отношении нашего веб-сайта, используется для составления отчетов об использовании веб-сайтов. Google будет хранить и использовать эту информацию. Политика конфиденциальности Google доступна по следующему адресу: https://policies.google.com/privacy .

Для работы сайта не обязательно включать файлы cookie, но это улучшает навигацию. Можно удалить или заблокировать файлы cookie, но в этом случае некоторые функции сайта могут работать некорректно.Информация о файлах cookie не используется для идентификации пользователей, и данные навигации всегда находятся под нашим контролем. Эти файлы cookie используются исключительно для целей, описанных здесь.

Как контролировать и изменять файлы cookie?

Вы можете изменить или отозвать свое согласие в любое время в декларации файлов cookie на наш сайт.

Политика конфиденциальности

Узнайте больше о том, кто мы такие, как вы можете связаться с нами и как мы обрабатываем личные данные, в нашем политика конфиденциальности .

Необходимые файлы cookie помогают сделать веб-сайт пригодным для использования за счет включения основных функций, таких как навигация по страницам и доступ к защищенным областям сайта. Веб-сайт не может нормально функционировать без этих файлов cookie.

| Имя | Поставщик | Цель | Срок действия |

|---|---|---|---|

| cookieConsent | Bid Inside | Сохраняет статус согласия пользователя на cookie для текущего домена | 6 месяцев |

| PHPSESSID | Bid Inside | Сохранять статус пользователя на разных страницах сайта. | Когда сеанс просмотра заканчивается |

| f_display | Bid Inside | Файлы cookie f_display запоминают режим отображения, выбранный пользователем на страницах, где есть списки. | Когда сеанс просмотра заканчивается |

| f_page | Bid Inside | Файлы cookie f_page хранят страницу, просмотренную пользователем, на страницах, где есть списки. | Когда сеанс просмотра заканчивается |

| f_rec_page | Bid Inside | Файлы cookie f_rec_page хранят количество элементов, которые должны отображаться на странице, выбранной пользователем на страницах, на которых есть списки. | Когда сеанс просмотра заканчивается |

| f_order_by | Bid Inside | Файлы cookie f_order_by хранят выбранный пользователем параметр сортировки на страницах, где есть списки. | Когда сеанс просмотра заканчивается |

| f_order_dir | Bid Inside | Файлы cookie f_order_dir хранят направление упорядочивания, выбранное пользователем на страницах, где есть списки. | Когда сеанс просмотра заканчивается |

| watch_list_show_imgs | Bid Inside | Файл cookie watch_list_show_imgs хранит выбор пользователя, отображать или скрывать изображения лотов на странице списка наблюдения | Когда сеанс просмотра заканчивается |

| selected_voice | Bid Inside | В файле cookie selected_voice хранится голос, выбранный пользователем для синтеза речи, присутствующий на живом аукционе | 1 Месяц |

| include_autobids | Bid Inside | Файл cookie include_autobids сохраняет выбор пользователя — показывать или скрывать свои auto-bid на странице «Ваши ставки». | 6 месяцев |

Аналитические файлы cookie помогают понять, как посетители взаимодействуют с веб-сайтом, собирая и передавая статистическую информацию контроллеру данных.

| Имя | Поставщик | Цель | Срок действия |

|---|---|---|---|

| _ga | Зарегистрируйте уникальный идентификатор, используемый для генерации статистических данных о том, как посетитель использует веб-сайт. | 2 года | |

| _gat_gtag | Используется Google Analytics для ограничения частоты запросов | 1 день | |

| _gat | Используется Google Analytics для ограничения частоты запросов | 1 день | |

| _gid | Зарегистрируйте уникальный идентификатор, используемый для генерации статистических данных о том, как посетитель использует веб-сайт. | 1 день | |

| __utma | Bid Inside | Используется для различения пользователей и сеансов. Файл cookie создается, когда библиотека javascript выполняется, а существующие файлы cookie __utma не существуют. Файл cookie обновляется каждый раз, когда данные отправляются в Google Analytics. | 2 годы |

| __utmt | Bid Inside | Используется для ограничения скорости запросов. | 10 минут |

| __utmb | Bid Inside | Используется для определения новых сеансов / посещений. Файл cookie создается, когда библиотека javascript выполняется, а существующие файлы cookie __utmb не существуют. Файл cookie обновляется каждый раз, когда данные отправляются в Google Analytics. | 30 минут |

| __utmc | Bid Inside | Не используется в ga.js. Набор для взаимодействия с urchin.js. Исторически этот файл cookie работал вместе с файлом cookie __utmb, чтобы определить, был ли пользователь в новом сеансе / посещении. | Когда сеанс просмотра заканчивается |

| __utmz | Bid Inside | Сохраняет источник трафика или кампанию, объясняющую, как пользователь попал на ваш сайт. Файл cookie создается при запуске библиотеки javascript и обновляется каждый раз, когда данные отправляются в Google Analytics. | 6 месяцы |

| __utmv | Bid Inside | Используется для хранения данных пользовательских переменных на уровне посетителя. Этот файл cookie создается, когда разработчик использует метод _setCustomVar с настраиваемой переменной уровня посетителя. Этот файл cookie также использовался для устаревшего метода _setVar. Файл cookie обновляется каждый раз, когда данные отправляются в Google Analytics. | 2 годы |

Предпочтительные / технические файлы cookie позволяют веб-сайту запоминать информацию, которая влияет на то, как сайт ведет себя или представляет себя, например, ваш предпочтительный язык или регион, в котором вы находитесь.

Мы не используем файлы cookie этого типа.Профилирующие файлы cookie используются в маркетинговых целях для отслеживания посетителей веб-сайта. Их цель - отображать релевантную и привлекательную рекламу для отдельного пользователя.

| Имя | Поставщик | Цель | Срок действия |

|---|---|---|---|

| _fbp | 6 months | ||

Неклассифицированные файлы cookie - это файлы cookie, которые классифицируются вместе с отдельными поставщиками файлов cookie.

Мы не используем файлы cookie этого типа.

60

60